Announcing our global conference in 2025

Shaping the future of AI in healthcareLatest news & blogs

Watch some of our members, Fellows and Officers talking about why they love working in radiology and oncology:

Not sure where to start on the site?

We've tried our best to make this new website more user-friendly, so you should be able to find what you need. If you're looking to explore, try one of the areas below to get started.

CPD & events

Log in to the Learning Hub

Upcoming Events

Supervisor Skills: Fully booked

This course is now fully-booked, express your interest for September 2024. The Supervisor Skills course introduces the General Medical Council (GMC) requirements for the roles of named educational and clinical supervisors and provides training for those roles to the GMC benchmark.

7 CPD credits- £180-

Annual Trainee Oncology Meeting (ATOM) 2024

The conference programme will cover a range of topics relevant to our field, including radical and palliative planning workshops, career progression, exam techniques and updates on hot topics in clinical radiotherapy.

10 CPD credits - Free

New consultants’ welcome event: The RCR working for you - Fully booked

This course is for RCR radiology and oncology members who are in their first year to 18 months in a new consultant post. Get updates on job planning, wellbeing, leadership skills and network with your peers from across the UK.

5 CPD credits - -

Management skills for radiologists (June) - Fully booked

Get practical updates on essential management tools to run an efficient and effective radiology department. This course is now fully booked. Bookings are now open on our Winter course (22 Nov-6 Dec).

16 CPD credits Supervisor skills - open for expressions of interest

This highly-popular course is for consultants, specialty doctors and senior trainees and introduces the General Medical Council (GMC) requirements for the roles of names educational and clinical supervisors to the GMC benchmark.

6 CPD creditsAdvanced Educational Supervisor - open for expressions of interest

For experienced educational supervisors to develop and implement strategies to maximise your trainees potential and provide support to CCT.

6 CPD credits- -

Management skills for oncologists

This intensive three-day course will cover all aspects on management, focussing on the skills and approaches required to effectively manage and run a busy UK oncology department.

20 CPD credits CR Research Day - open for expressions of interest

If you’re interested in a career in research, join us in-person and hear expert radiology speakers share their insights and the challenges they faced in carving out their academic niche.

5 CPD creditsCO Academic Day

This course is essential for those interested in research. This year’s theme will focus on advanced technologies in clinical research. Hear from experienced academics and share your ideas with our expert faculty.

5 CPD credits- -

5th National RCR Radiology Events and Learning Meeting (REALM)

For clinical radiology trainees and consultants, our fifth annual REALM course will be held at the Robinson College, University of Cambridge and will bring together internationally renowned speakers to discuss why radiologists can never be certain and how we deal with uncertainty.

13 CPD credits CO new trainee welcome event - open for expression of interest

We would like to welcome all newly appointed clinical oncology trainees to this introductory event as we explain the role of the College and how trainees can work together with us.

CR new trainee welcome event - open for expression of interest

We would like to welcome all newly appointed clinical radiology trainees to this introductory event as we explain the role of the College and how trainees can work together with us.

Clinical Radiology Artificial Intelligence (AI): Blended learning course

Delivered by our expert AI faculty and for radiologists and allied healthcare professionals at any level of training or experience, this blended learning course will give you a global overview of AI in radiology and what it means for the specialty. Express your interest to receive priority booking when registration opens.

12 CPD credits- -

Management skills for radiologists (November/December)

Get practical updates on essential management tools to run an efficient and effective radiology department.

16 CPD credits 3rd Annual RCR BSPR Study Day: Paediatric Trauma and Injuries

A comprehensive and interactive virtual day focussing on imaging injury and trauma in the child. Topics span body imaging, contrast US, trauma in abuse and neuroradiology.

5 CPD credits- -

Shaping the future of AI in healthcare: Learning from practice - Global AI Conference 2025

Join us at our 1st Global AI Conference as we bring together leading doctors, policy makers, educators and innovators to share clinical expertise and best practice and discuss the latest cutting-edge developments in this rapidly moving area of healthcare.

- Free-

RCR Equity and Allyship in Practice (REAP) : a webinar series

As part of our commitment to supporting equity, diversity, and inclusion we have developed the RCR Equity and Allyship in practice (REAP) programme.

5 CPD Credits - Free

Webinar: Expert panel recommendations for radiotherapy treatment for vulval cancer guidance

This free webinar will include an introduction to the vulval cancer guidelines, providing the background to how it was developed and an overview of the key points. There will also be an opportunity for audience Q&A.

1 CPD credit Managing underperforming colleagues

In this short webinar, Dr Ashley Shaw shares his approach to managing the challenges presented when managing colleagues, and navigating the difficult conversations when maintaining performance within the team.

Develop your career

Publications

A collection of all our publications, including those for radiology and clinical oncology; radiotherapy consent forms; QSI; and our three journals: Clinical Oncology, Clinical Radiology, and RCR Open.

Research & academia

We actively encourage those interested in academic radiology and oncology: research allows us to demonstrate benefits through clinical trials and to improve the quality of imaging. Find out more about research & academia in our specialties below.

Management & service delivery

Want to know more about the ways in which we support service delivery across our specialties? This hub is the place to start: you'll find our QSI, service review, national radiotherapy consent forms and much more.

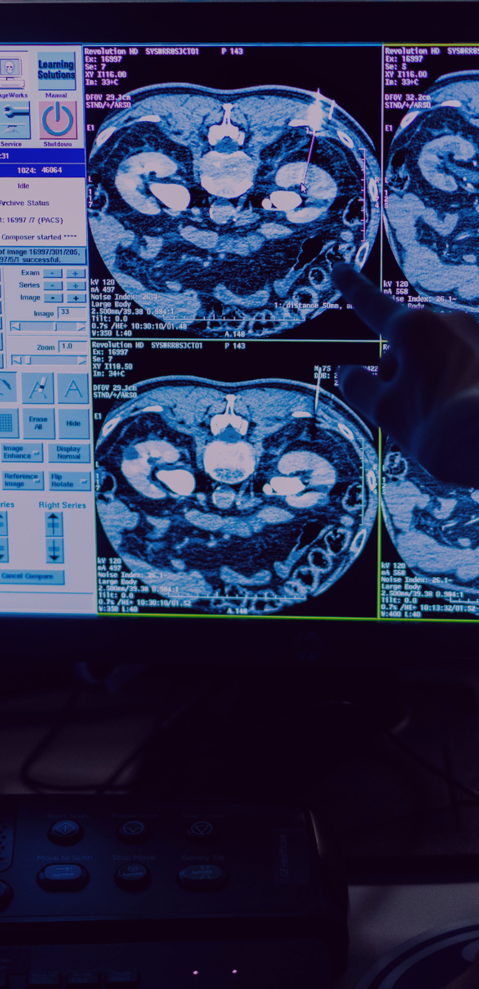

Artificial intelligence (AI)

Artificial intelligence is the phrase of the day. Conversations are happening across the globe to discuss how it could improve healthcare, and the risks and benefits in each scenario. The Royal College of Radiologists is working hard to be the voice of our specialties when it comes to AI in healthcare.

Who we are

The Royal College of Radiologists is a charity that works with our members and Fellows to improve the standard of medical practice across the fields of radiology and oncology. With faculties in two disciplines, the College and our members benefit from a fuller understanding of medical practice, across the spectrum of diagnosis and treatment.

Become a member today

With over 16,000 Fellows and members worldwide, The Royal College of Radiologists exists to lead, educate and support doctors who are training and working in the specialties of clinical oncology and clinical radiology. With such a broad perspective on our two specialties, we develop and deliver a unique body of work which could not be undertaken by any other organisation.

Discover your pathway

The Royal College of Radiologists leads, educates and supports doctors who are training and working in the specialties of clinical oncology and clinical radiology.